How was the Gaol run?

By the time the Melbourne Gaol was built ideas about how criminals should be punished were changing.

- So what did the new gaols look like and how were inmates treated?

- How was this different to Australia’s earlier convict history?

- And why was prison now considered a way of preventing crime?

Please note that images and names of deceased Indigenous people are contained within this webpage.

New Ideas

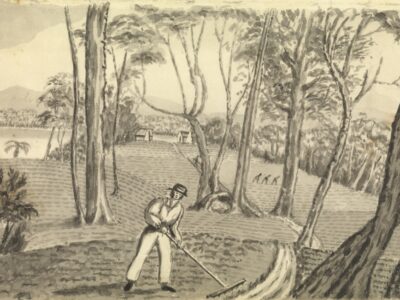

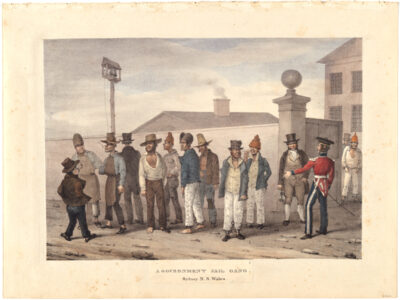

The experience of most convicts sent to Australia during the first 50-70 years of settlement was one of labouring – either in government work gangs, or as assignees to other colonists. Gaols weren’t a large part of the system. Transportation was seen as an alternate form of punishment and as an answer to the problem of soaring crime rates in England.

While early 19th century society believed in punishing criminals – often through severe punishments like hanging or transportation – this had not halted the growing crime rate. By the mid-century attitudes were changing. New ideas were explored – ideas about how punishment could be used to stop criminals from re-offending in the future.

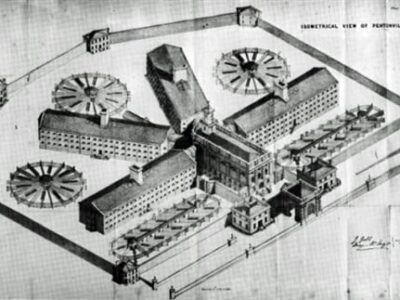

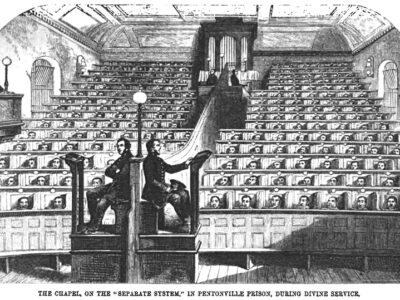

In 1842 Pentonville prison in England was opened and run using a new style of operating system. An improvement on the existing prisons – in which men, women, serious and petty criminals had been massed together – it separated prisoners into different classes. Incorporating contemporary ideas of reforming the criminal classes, it became the ‘model’ for prisons around the world.

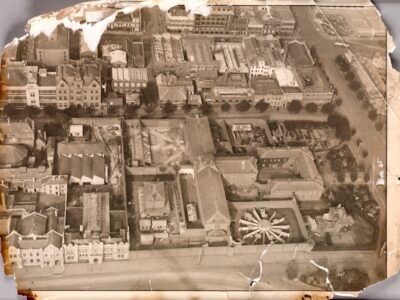

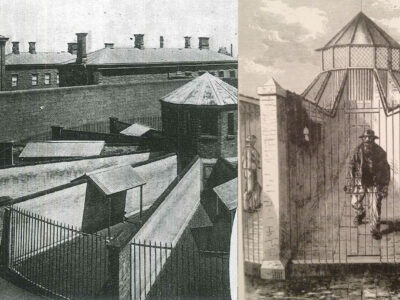

The design of the Melbourne Gaol – along with many other gaols built in Australia at that time – was inspired by ‘model prison’ specifications. It provided for the separate confinement of prisoners, in cellblocks that radiated out from a central observatory. At each angle of the perimeter wall was a tower for the purpose of overlooking the establishment.

The Model Prison System

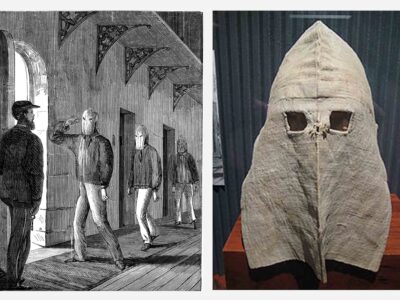

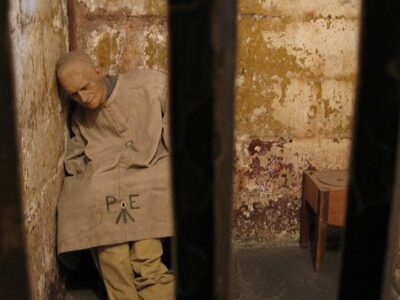

The philosophy of the ‘Model’ Prison was silence and separation. Prisoners were kept in isolation, with minimum distractions, in the belief they would be able to reflect on their crimes, realise the error of their ways and then reform. When a prisoner left their cell a canvas ‘silence’ mask was worn to keep them isolated from other prisoners outside their cell.

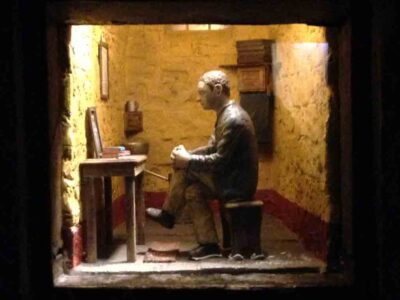

Prisoners began their sentence in solitary confinement cells – measuring 2.7 x 1.5 metres. Here they were locked up for up to 23 hours a day. Inside was a thin straw mattress, a blanket, a stool, a small table, a toilet bucket and a bible. Daily activities such as meals, prayers, work and sleep were governed by bells that rang out in the cellblock.

Rules & Punishment

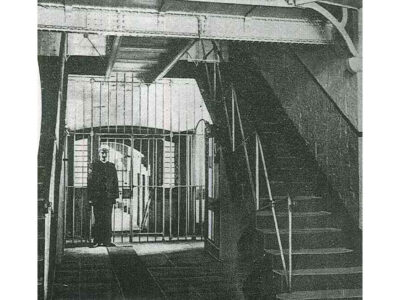

The movement of prisoners around the gaol was regulated by bars and doors. In time, prisoners would progress through the system – going out to work during the day, and even spending time in a communal cell. Like any institution the Gaol needed rules to function efficiently. Regulations were strict – talking, singing, laughing, gambling and tattooing were prohibited and prisoners had to keep themselves and their cells clean and tidy.

New attitudes to criminal justice in the nineteenth century brought a change of emphasis from simple punishment to the idea that punishment should be used as rehabilitation for prisoners – to change them into better people. Part of this was the idea that criminals must be shown the value of working for a living, which resulted in the concept of hard labour.

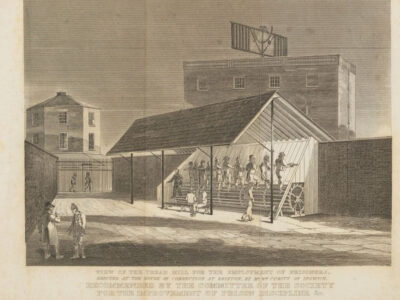

But prison also needed to act as a deterrent, so people would want to avoid being sent there. One form of punishment designed to be demoralising and serve no purpose other than the effort of carrying out the task itself, was the ‘treadmill’. By pedalling the wheel – like a mouse wheel – prisoners could be made to climb steps for hours.

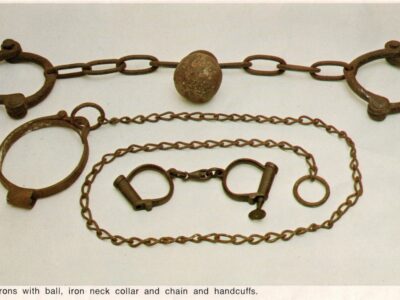

Rules were enforced through a hierarchy of punishments. Minor infringements attracted withdrawal of privileges – such as the removal of rights to receive letters or visitors, or having rations cut back to bread and water. Disorderly prisoners were kept in chains and could be held in punishment cells on the ground floor.

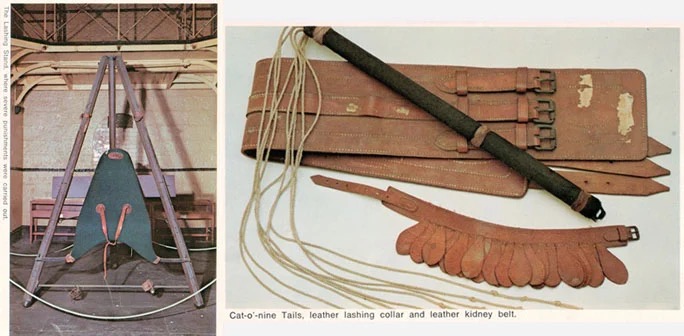

For serious breaches of discipline there was the cat-o’-nine-tails. Male prisoners over 16 years of age were strapped, shirtless to the lashing triangle. Their back would then be lashed with the ‘cat’ – a whip consisting of nine strands of knotted cord. The flagellator was usually a fellow prisoner who was paid to do the job. Women were never subjected to corporal punishment.

Legacy

Far from successful, the Model Prison system did little to reform criminals, and the harsh, lonely conditions often led to mental breakdown. By the end of the Victorian era reformers were arguing that it hardened rather than deterred criminals. Notions of born ‘criminal classes’ gave way to the understanding that the root cause of crime for many people was simply poverty.

However the influence and legacy of the Model Prison system remains current to this day. Penitentiaries, ‘panoptican’ design and solitary confinement all form a part of modern correctional institutions. And while punishment itself is no longer believed to reform prisoners, rehabilitation is considered an important element of contemporary criminal justice.

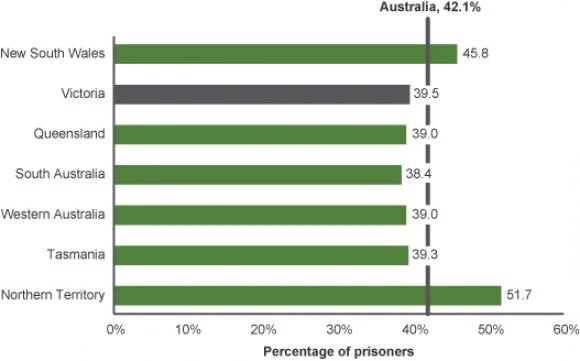

The question of how successfully the prison system rehabilitates offenders remains as relevant today as it did in the past. In 1874, 30% of male prisoners at the Melbourne Gaol had been previously convicted (1,044 of 3,548). According to 2011-2012 data, what is the repeat offending rate for Victorian prisoner’s, within two years of release?

Things to think about

Years 5-6

- Explain why the Pentonville style of gaol was popular in prison design globally.

- Suggest how the practice of ‘silence and separation’ was thought to change behaviour.

- Summarise the routine of daily life for a prisoner incarcerated in the ‘model’ prison system.

Years 7-9

- Explain how the idea of a criminal class shaped the development of gaols in Victoria.

- Consider what the long-term effects of the ‘silence and separation’ system of punishment would have been on a prisoner.

- Reflect on the appropriateness of using corporal punishment to achieve reform – both then and now.

Years 10-VCE

- Extrapolate on the interrelationship between a ‘criminal class’ and the development of purpose-built Pentonville-style gaols.

- Reflect on the impact of the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution in the establishment of the Victorian-era prison system.

- What conclusions can be drawn by comparing 19th century rates of recidivism with present day figures for Victorian prisons?